Diabetic Eye Disease

Diabetes is the leading cause of visual impairment in the United States among patients below the age of 50. Many patients who suffer a loss of vision first present for eye examination when unknown to the patient, the eye disease is already advanced. A few others lose vision despite meticulous eye care. With proper and timely treatment, the likelihood of losing vision as a result of diabetic eye disease is significantly decreased.

Diabetes is the leading cause of visual impairment in the United States among patients below the age of 50. Many patients who suffer a loss of vision first present for eye examination when unknown to the patient, the eye disease is already advanced. A few others lose vision despite meticulous eye care. With proper and timely treatment, the likelihood of losing vision as a result of diabetic eye disease is significantly decreased.

Diabetes is primarily a disease of tiny blood vessels, called capillaries, the thin vessels that connect veins and arteries and act in the circulatory system as the loading docks for nutrients, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and waste products. The damage to the capillaries is cumulative and, as we understand it, dependent upon the total time and amount that the blood sugar is above normal. In insulin-dependent diabetes, where the onset is often very abrupt, this accumulation of the effects of abnormal blood sugar rarely shows up as a visual problem until at least five years after initial diagnosis. In adult-onset non-insulin-dependent diabetes, eye disease can show up earlier because diabetes may have been smoldering at a low level for several years before the diagnosis is actually made.

Diabetic Retinopathy

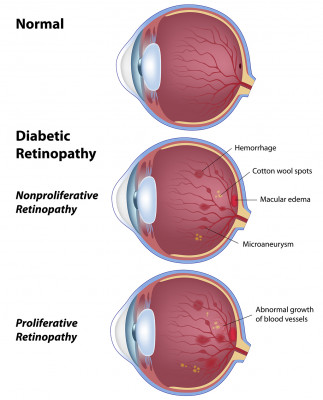

Long-term damage to capillaries in the eye manifests itself especially in the retina, resulting in diabetic retinopathy. Macular swelling (macular edema) can result from damaged capillary walls becoming abnormally permeable. The growth of new blood vessels (proliferative diabetic retinopathy) can result from the complete clogging of large beds of capillaries. These problems develop separately and sometimes together.

In the early stages, only tiny dots of red cells that have escaped from damaged capillaries into the retinal tissue (dot hemorrhages) and outpouchings of the walls of tiny blood vessels (microaneurysms) can be seen. This is called background diabetic retinopathy. Damage to blood vessels can then proceed down two paths with two visual results and two treatments. One problem, macular swelling (macular edema), results from damaged capillary walls becoming abnormally permeable. The other problem, the growth of new blood vessels (proliferative diabetic retinopathy) results from the complete clogging of large beds of capillaries. Sometimes these problems develop separately and sometimes together. We will discuss them as if they occurred separately.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

When whole beds of capillaries close off and fail to carry necessary oxygen and nutrients, the tissue starves. Starving retinal tissue sends out a chemical message (angiogenesis factor) that asks for new blood vessels to grow. Unfortunately, because of the structure of the eye, the resulting new blood vessels grow in the wrong place, usually off the surface of the retina into the vitreous in the interior of the eye. In that location, they are subject to being tugged upon by the shrinking vitreous jelly. This tugging often produces bleeding in the eye, which the patient sees as strings and specks that usually develop suddenly, often overnight. Each spot where new blood vessels grow also tacks the vitreous to the retina, establishing a point at which the retina can be elevated or torn by later contraction of the vitreous. Before laser treatment for this condition became available in the late 1960s, ophthalmologists knew that a diabetic eye that presented with vitreous hemorrhage had a 50 percent chance of becoming stone blind within three years. With timely treatment today, only 1 or 2 percent of such eyes will become completely blind.

Laser treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy is more involved than macular edema. Ultimately, 700 and 2000 burn spots are made in the peripheral retina. This substantial cauterization destroys much of the starving retinal tissue. The dead retinal tissue no longer asks for new blood vessels to grow, resulting in cessation of growth and often shrinkage of the new blood vessels observed. Because this does not happen instantaneously, it is possible to perform a laser treatment and have further vitreous hemorrhage occur after the treatment.

Although this is a significant nuisance, the natural history of vitreous hemorrhage is to gradually clear. Unfortunately, such clearance can take several months. If laser treatment has been placed before the hemorrhage, the new blood vessels that caused it will wither rather than grow. Therefore, the ultimate visual outcome is expected to be better in those eyes with prior treatment.

Unlike the treatment for macular edema, the laser treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (called panretinal photocoagulation) is usually done with a local anesthetic injected into the tissue near the eye (and not into the eye itself) with a long, thin needle. After placing the local anesthetic, the eye goes either partially or completely "to sleep," so the treatment can be performed entirely painlessly. The anesthetic sometimes produces temporary double vision, which is best relieved by patching one eye for several hours.

When the eye wakes up, there is sometimes a headache or brow ache, which usually is relieved with acetaminophen or, in the unusually severe case, with ice held over the closed eye. Head elevation and avoidance of heavy lifting and strenuous exercise can also be helpful during the early period following the treatment. The eye may be light-sensitive. Sunglasses help.

Vision is often blurry for a few days and moderately blurry for as long as a few months. Initially, there are many shimmering specks in the peripheral part of the vision corresponding to the areas of laser treatment. This gradually fades over a period of months.

Although the dramatic appearance of the peripheral retina after one treatment, central and peripheral vision is often very good. A few eyes lose some of the sharpness of the central vision around the time of such treatment. It is impossible to know whether this is because of the progression of the smoldering diabetic retinopathy or if it is actually a direct consequence of treatment. Because of that small chance of vision not improving, we tend to wait to perform treatment until it is evident that the small risks of treatment outweigh the risk of continued observation.

Diabetic Visual Changes Which Are Not Retinopathy

Besides the accumulation of damage to small blood vessels because of high blood sugar, the level of blood sugar can more directly affect vision. Fortunately, these direct effects are not permanent. When the blood sugar is over about 200 for several hours or several days, the blood sugar causes the lens in the eye to swell and produces temporary nearsightedness. This effect goes away once the blood sugar is corrected to a normal level. This effect causes many adult-onset diabetics to experience severe visual blurring during the month immediately after diagnosis when blood sugar is gradually brought into the normal range.

On the other end of the spectrum, some diabetics experience peculiar visual symptoms as the first hint of hypoglycemia, the circumstance when the blood sugar is so low that the brain and eyes are not being adequately fed.

Diabetic Macular Edema

Patches of capillaries damaged by high blood sugar may leak serum, including fat and protein, into the adjacent retinal tissue. This tissue swelling causes the retina in that area to malfunction. If the affected area involves the center of the retina, blurry vision results will gradually develop. Surgery to reduce macular swelling is done using the laser sometime during the next several months.

The exact location of the leaks can be demonstrated by a test called fluorescein angiography. This is a test done in the office using a fluorescent dye injected into the large vein in the crook of the patient's arm. Photographs are taken of the back of the eye with ordinary light, not X-rays. The leakage characteristics of the dye define the areas of damage to the capillaries. A laser can be used with a fine light beam to focally cauterize the leaky spots by utilizing the fluorescein angiogram as a sort of roadmap. This often results in the swollen tissue drying up.

A meticulous clinical study about 10 years ago demonstrated that when such treatment was properly applied, treated eyes were, on average, seeing better at three years after the treatment than eyes not treated. (It should be noted that some eyes lose substantial amounts of central vision even with optimal laser treatment due to the progression of the underlying diabetic disease). The treatment helps the eye preserve its vision rather than produce visual improvement. The treatment is very minor from the patient's perspective. Many patients have noted that the treatment is less of a nuisance than the fluorescein angiogram necessary to perform it.

The reduction in macular swelling accomplished by the laser develops only gradually over the next two to four months. Usually, if further treatment is necessary or desirable, it is not performed on the same eye until about four months have passed. For several months following the laser treatment, some patients were aware of some tiny blank spots in the vision near the center that corresponded to the actual locations of the laser burns. This perception gradually fades, but the fading occurs slowly.

Prevention

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) proved conclusively that the better the blood sugar control as measured by hemoglobin A1c, the less severe the progression of diabetic retinopathy. We all hope that one day, we can routinely normalize blood sugar with a transplant or implant. In the meantime, you can help save your vision, heart, kidneys, and feet by working with your regular medical doctor to control your blood sugar closely.

You cannot benefit from preventive treatment unless you know that you need it. It is essential to be e. In the complete absence of retinopathy, re-examination should be done yearly or, under certain circumstances and at the direction of your eye physician, once every two years.

To schedule an appointment, call (509) 456-0107